Jan 7 2026

~10 minutes

Mind the Gap

SQL stories seem to be very popular on this blog... Maybe it's because they're so relatable and everyone joins in.

Thank you, thank you. I'll be here all week. Aaanyway... If you haven't read my previous tiny introduction to the Transactional Outbox Pattern, go and give that a quick read. It's okay. I'll wait. Okay, caught up?

Cool. Let's dive into some of the challenges, quirks and gotchas that my team and I experienced when implementing this pattern in a fairly large service.

Indexs? Indices? Indexi? Indexes! :)

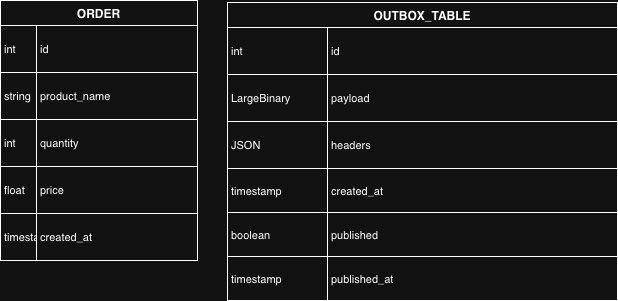

As a reminder from the previous post, here are the DB tables we're dealing with:

However, what I didn't include in the previous post is additional info about indexes on the outbox_table table

(and yes, I looked it up, apparently 'indices' is math-related, whereas 'indexes' is appropriate for DBs. The more you know and all that).

Another thing I didn't include is that we're working with MySQL 8.0 with InnoDB engine. Why does that matter? Oooh, you'll see soon enough, dear sweet innocent reader.

We have this migration for our outbox_table table:

1 CREATE TABLE `outbox_table` (

2 `id` bigint unsigned NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

3 `payload` blob NOT NULL,

4 `headers` json NOT NULL,

5 `payload_type` varchar(255) NOT NULL,

6 `published_at` datetime DEFAULT NULL,

7 `created_at` datetime NOT NULL DEFAULT (UTC_TIMESTAMP()),

8 PRIMARY KEY (`id`),

9 INDEX `idx_outbox_table_created_at_published_at` (`created_at`, `published_at`));

You'll notice that we created a composite index on the created_at, published_at fields. This bit is important, so remember it for later.

Locked in

Our outbox_publisher's job was the following:

- Fetch all records in the

outbox_tabletable that were not yet published, with preconfigured batch limit (let's say 25). So, any rows within our limit that had aNULLpublished_at - Publish all the events for any rows fetched.

- Update the published records with the appropriate

published_attimestamp.

As most of you will know, developers add indexes to DB tables to speed up certain queries. In this case, our select query looked like this:

1SELECT *

2 FROM outbox_table

3 WHERE published_at IS NULL

4ORDER BY created_at

5LIMIT ?

6FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED;

Those DBAs-in-waiting among you will notice a few things right away:

1SELECT … FOR UPDATE

A select for update statement does the following:

- It acquires exclusive row locks on the selected rows

- As such, it guarantees that no other transaction can modify or delete those rows until the current transaction is committed or rolled back.

Prevents: So this is a protection mechanism against:

- two (or more) workers selecting the same unpublished rows simultaneously before either worker updates them.

- race conditions between the SELECT and UPDATE statements

1SKIP LOCKED

This tells the DB to not wait up by the phone if this row is ~~out with the bois~~, I mean, locked by another transaction. It prevents workers from blocking each other, and also allows you to scale horizontally by adding more workers since they can read from the same table effectively.

Without SKIP LOCKED, the second worker would either block until the first worker commits or even worse, we'd have a deadlock on our hands.

Shards and Sharts

Why do we need all this complexity? Why not just do a simple select and update? Glad you asked! See, we're not dealing with your average, run-of-the-mill, small-scale, grandmother's application here. We're dealing with a high-throughput system with a sharded database setup.

Potential accidental underwear soiling jokes aside, a sharded database means that our data is partitioned across multiple database instances, or shards, based on a certain key (like a user ID). This allows us to distribute the load and improve performance, but it also introduces some challenges when it comes to ensuring data consistency and avoiding conflicts between workers.

I can already hear some of you thinking: "Why not just have one worker per shard?"

Well, yeah... that's what we have. However, in this wonderful world of microservices and container orchestration, things can get a bit... unpredictable.

As such, there is a non-zero chance that two workers could end up working on the same shard at the same time. Hence, the need for SELECT FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED.

Gaps & Ghosts

Alright, so we have our select query with FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED, and we're ready to roll. Or so we thought. After shipping this setup to production, we started noticing some weird behavior, mostly with latency spikes on the INSERT operations on the outbox table.

After doing the initial checks, we started to suspect our old friend the SELECT FOR UPDATE query. To confirm our suspicions, we enabled the general query log in MySQL and started analyzing the logs. And sure enough, we're seeing quite a bit of locking happening on some of these rows. But wait, didn't we instruct the SELECT query to skip locked rows? Yes, we did. So what does this have to do with the INSERT operations?

Turns out, there's a little-known behavior in MySQL's InnoDB engine related to gap locks and the way indexes work. A gap lock is a lock on a gap between index records OR a gap before the first or after the last index record. This last one is important.

When we have a composite index on created_at and published_at, the SELECT FOR UPDATE query can acquire a gap lock on the index ranges, not just the rows themselves. It does this to prevent phantom reads.

What's a phantom read? It's a concurrency phenomenon where a transaction reads a set of rows that satisfy a certain condition, but another transaction inserts new rows that also satisfy that condition, leading to 'phantom' rows that weren't there on the initial SELECT.

Typically, range selection phantom issues are handled by setting the REPEATABLE_READS at the MySQL server level. With the InnoDB engine, this configuration uses something called 'next-key locking'. According to the docs, this strategy combines index-row locks with "gap locks" to lock the space between rows, preventing other transactions from inserting new rows within that range.

But are we dealing with range selections? Well, not really.

1SELECT *

2 FROM outbox_table

3 WHERE published_at IS NULL

4ORDER BY created_at

5LIMIT ?

6FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED;

So what gives? Not every single INSERT was getting issues, just some of them. Once again turning to the almighty docs, it turns out that the REPEATABLE_READ isolation level and next-key locking can still lead to gap locks being acquired in certain situations, even if we're not doing range selections. InnoDB will lock the space between the records in the index, in order to protect against phantom inserts. But we're using the skip locked clause, so why are we still seeing issues?``

After digging deeper, we found out about something called the 'supremum lock'. I'll let the official documentation explain it best:

Suppose that an index contains the values 10, 11, 13, and 20. The possible next-key locks for this index cover the following intervals, where a round bracket denotes exclusion of the interval endpoint and a square bracket denotes inclusion of the endpoint:

(negative infinity, 10]

(10, 11]

(11, 13]

(13, 20]

(20, positive infinity)

For the last interval, the next-key lock locks the gap above the largest value in the index and the “supremum” pseudo-record having a value higher than any value actually in the index. The supremum is not a real index record, so, in effect, this next-key lock locks only the gap following the largest index value.

This is particularly relevant to us because it can cause locking when attempting to insert records at the end of an index range. So we basically had our insert and select queries doing the following:

MAX to the rescue?

What do we know so far about the issue?

- We have

INSERToperations that are getting blocked due to next-key locks, since they affect the index on the table. - InnoDB is doing its job in protecting against phantom reads and offering reliable transaction isolation.

- This causes issues for our

INSERToperations, leading to deadlocks and just generally a bad time. - Thankfully, thanks to the outbox_publisher design, no events are lost since the entire transaction rolls back if the insert fails.

So how did we fix this? (yeah, we did fix this, otherwise I wouldn't be writing this post, now would I?)

Given our problem relates to the ranges covered by the composite index on created_at and published_at, we decided to try and do something about that instead. What if, instead of selecting the entire range covered by the index, we ... you know... don't? We basically figure out the last committed transaction's primary key and select everything before that?

1SELECT MAX(id)

2 FROM outbox_table

3 WHERE published = 0

(the keen readers among you might have noticed we no longer care about the published_at column, in favour of the published boolean column. This was part of the multiple attempts to improve the situation, but this post is already getting too long so let's just run with it, k? k!)

Anyway, with that max ID in hand, we can now do a select like this:

1SELECT *

2 FROM outbox_table

3 WHERE id < <max_unpublished_id>

4 AND published = 0

5ORDER BY id

6LIMIT ?

7FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED;

By using our max_id, we are explicitly pruning the search space the DB has to do. So, InnoDB does not need to lock the gap above the highest ID in the table, only the rows below it.

So, by using the following:

LIMITclause- id <

max_unpublished_id SKIP LOCKED- proper indexing

Another crucial point is that since we're working with id, which is an auto-incremented primary key.

Because of this predictable range, we can now prevent InnoDB from locking the gap above our selected rows and no longer stalling our INSERT operations. Yay and such!

So what's next?

Well, ideally, we shouldn't even have had to do any of this. The keen among you may have noticed that the main reason we were running into these issues is because of that darn SELECT FOR UPDATE itself. If we could avoid using it, we could avoid all these issues. So... did we remove it? That, my friends, is a story for another day.

Stay tuned for the SQL! (haha, get it? SQL? Sequel? sigh. Never mind...I'll see myself out.)