Dec 10 2025

~5 minutes

Goin' Postal

Intro: Dopamine & Distractions

As the year draws to a close, the usual talk of New Year's resolutions starts buzzing around.

I never understood these motivational videos on Youtube or self-help blogs that talk about 'sharing your plans' with your friends. I guess the idea is to create accountability so you'll actually follow through. For me though, this has the opposite effect. I get the dopamine hit from telling everyone, then my brain full-on backstabs my ambitions and witholds the sweet sweet happy hormones. So naturally, I don't do the thing I talked about.

Far-fetched analogy, I know, just bear with me ok? At least it's somewhat better than your average LLM (not really but hey).

Why am I rambling on about this? Well, this pattern is basically what my backend services were stuck in. They would tell everyone about their cool sh*t (aka publishing event messages) and get their little dopamine hit, but then their actual work (DB transaction) would fail.

This was always "fun", since it led to lovely bugs. Much like you and your friends, where you continued living your life assuming your cool friend was off doing all the cool things they were bragging about, the downstream consumers of the event messages were now assuming that the publisher service had successfully completed their transaction. When it then turns out their dopamine addicted *ss didn't actually do the work, we had some neat issues on our hands. Partial failures, data inconsistencies across services, retries causing deduplications, inconsistent reads in downstream systems... you name it!

Transactional Outbox Pattern

Because we got pretty sick of debugging these type of issues, we set about investigating how to avoid some of these issues in the first place. After all, why would you emit an event when your main DB transaction might fail and be rolled back?

Enter the OutBox Publisher Pattern. One of the key guarantees this pattern provides is to use the primary database transaction to record both the domain change AND the intent to publish the event.

It does this by writing both the initial record (e.g. a croissant order) AND the event message metadata and payload to the DB. Next, an asynchronous process can then poll or stream entries in the outbox table, handle the publishing of the event and finally mark the event as dispatched. A secondary process can then periodically clean up the dispatched records so your outbox table doesn't grow too large.

Anatomy of the Outbox Table

Let's dive into a simplified example. Lets say we are running a bakery frontend with an async event system to process the orders in our backend bakery (just roll with it okay, I'm running low on creative analogies here)

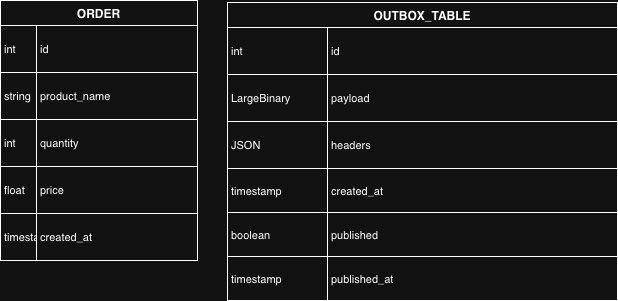

In our primary service we have a database with two tables:

The main constraint for the outbox_publisher table is that each payload is IMMUTABLE. We don't want to mess with event payloads or metadata at all. IF the original record (aka the croissant order) is updated or deleted, we enter a new event in the outbox_publisher table which the downstream consumer services can then handle separately.

Publish & Purge

Now that we have our primary record AND event record successfully written to the database, we can kick off our little postal worker process. This worker can poll for any new entries to the publisher table, handle the publishing of the event, then mark the event as published using the boolean column).

This works beautifully. However, over time and in high-throughput systems, this outbox table can grow quite large. Sure, now we can look at partitioning or other ways to handle that read load, but for simplicity we can just delete any of the dispatched event records.

To do this, we can have a second worker run periodically, check for all outbox records marked as published and delete them. To give ourselves some margin we can only delete records that were published more than 2 weeks ago. This is neat because it allows us more visibility for debugging.

Computer Says No

So when does something like the outbox pattern not fit the bill? When dealing with relational databases that have strong transactional guarantees, this pattern is amazing. For non-transactional systems or in systems where ordering is critical, this might not work very well. But then again, if ordering is critical, what are you doing with async event publishing anyway? :)

In that case, it's better to consider things like CDC pipelines, streaming pipelines or log-based setups. We won't dive into those here.

Enough talk. Show Code

Okay okay, chill. Here it is:

1class Order(Base):

2 __tablename__ = "orders"

3 id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

4 product_name = Column(String, nullable=False)

5 quantity = Column(Integer, nullable=False)

6 price = Column(Float, nullable=False)

7 created_at = Column(DateTime, default=datetime.datetime.utcnow)

8

9class Outbox(Base):

10 __tablename__ = "outbox_table"

11 id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

12 payload = Column(LargeBinary, nullable=False)

13 headers = Column(JSON, nullable=False)

14 created_at = Column(DateTime, default=datetime.datetime.utcnow)

15 published = Column(Boolean, default=False, index=True)

16 published_at = Column(DateTime)

17

18def create_order(product_name, qty, price):

19 # Create both the order and outbox record and commit to DB

20 s = Session() # fake session from SQLAlchemy for brevity

21 try:

22 order = Order(

23 product_name=product_name,

24 quantity=qty,

25 price=price

26 )

27 s.add(order)

28 s.flush() # order.id now available in SQLAlchemy session object

29

30 payload = {

31 "event": "OrderCreated",

32 "data": {

33 "order_id": order.id,

34 "product_name": order.product_name,

35 "quantity": order.quantity,

36 "price": order.price,

37 "created_at": order.created_at.isoformat()

38 }

39 }

40

41 outbox_entry = Outbox(

42 payload=json.dumps(payload).encode("utf-8"),

43 headers={"content_type": "application/json"}

44 )

45

46 s.add(outbox_entry)

47 s.commit() # atomic

48 return order.id

49

50 except Exception:

51 # NOTE: entire transaction gets rolled back, so entity AND event, even if only one of them fails

52 s.rollback()

53 raise

54 finally:

55 s.close()

56

Next, we have our OutboxPublisher worker that runs continiously in a separate deployment.

1

2class OutboxPublisher:

3 def __init__(self, outbox, publisher, batch_size=50, delay_sec=1):

4 self.outbox = outbox

5 self.publisher = publisher

6 self.batch_size = batch_size

7 self.delay_sec = delay_sec

8

9 def run(self, should_stop):

10 while not should_stop():

11 start = time()

12 more = self.process_batch()

13 elapsed = time() - start

14

15 if not more:

16 sleep(max(0, self.delay_sec - elapsed))

17

18 def process_batch(self):

19 with session.begin():

20 messages = self.outbox.get_unpublished(self.batch_size)

21 if not messages:

22 return False

23

24 published = []

25 for m in messages:

26 try:

27 self.publisher.publish(m.payload, m.headers)

28 published.append(m)

29 except Exception:

30 continue

31

32 self.outbox.mark_published(published) # simply updates the outbox_record to `published = 1` and the `published_at with current timestamp`

33

34 return len(messages) == self.batch_size

Lastly, a cleanup worker that can be configured to delete published records that are of a certain age.

1def delete_published_before(outbox, before_date, limit=500):

2 total = 0

3 while True:

4 with session.begin():

5 deleted = outbox.delete_published_before(before_date, limit)

6 if deleted == 0:

7 break

8 total += deleted

9 return total

10

Closing Notes

So, with just a handful of code and a bit of infra / DB work, we're now in a much better place where we can reliably tell the world about the cool shit we're doing, and make sure we've actually done it! :)

Even if our publisher crashes mid-flow, this pattern should allow enough resilience to never lose messages and give our developer team same extra buffer to debug and investigate.

In the next part of this two-part series, we'll dive into some interesting operational considerations and gotcha's that have bitten us in the backside since implementing this pattern in some of our high-throughput services and how we mitigated some of the most common issues. Stay tuned for that, hopefully it won't take another year!